Miami, Indian Territory, came into existence on March 2, 1891. A transplanted Kansan, Wayland C. Lykins, envisioned a brand new town. He had to travel to Washington D.C. in order to get approval of a township patent. While there, he met Thomas P. Richardville, chief of the Miami tribe. With Richardville’s help, i.e. speaking to the U.S. Indian Commissioner, and Lykins purchasing the needed property with the blessing of chief Manford Pooler of the Ottawa Indian tribe (again, with Richardville’s help), the town was born.

Lykins invited Richardville to name the town, and he chose the name of his tribe as a suitable moniker. Pronounced Mi-am-UH!

Furrows were plowed across the prairie marking city streets. Townsite company offices were opened at the present-day site of Osborn Drugs on West Central. The first deed was held by Dr. W.L. McWilliams, which he used to construct his two-story house at the corner of E. Central and B.

The first store was a 14 x 20 foot structure built by G.W. Bingham, located where the city hospital now sits. It opened for business on June 11.

The town’s first drug store was built that same year of 1891 by Dr. W.L. McWilliams. It sat on South Main, across from where the fire station would be. McWilliams’ most enduring legacy was built in 1892, at the SW corner of Central and Main. It was a two-story structure which, in 1901, received a third, and which became Miami’s vaunted McWilliams Opera House.

Unknown carriage shop, early 1900’s. Probably located on S Main

At the time, that corner was so far removed from the main part of town that many joked that his building was out in the country! The main business locale was two blocks south. Incidentally, McWilliams became Miami’s first postmaster in 1895.

On December 1, 1892, Clarence Miami Page was born, Miami’s first baby. Clarence would go on to become a miner, as would many other Miami men. By 1909, there were plans for an electric railway to Picher, making commuting simple. More on that a little later.

There was a law preventing the sale of liquor on Indian land. But the privately-owned town now was open for booze. By 1895, there were four saloons operating, when city government was finally formed. Under Miami’s first mayor, H.H. Butler, local legislation was quickly passed banning them. It would be after prohibition’s repeal before Miami would once again have bars.

L.B. Zilar became the town’s first photographer, and many early Miami photos were actually his work. His wife Martha opened Miami’s first clothing store, at present-day 101 S Main.

In 1896, the first train rolled into Miami. Lykins donated $30,000 in property so that the Kansas City, Ft. Scott, and Memphis Railway would run tracks into town. By 1901, Frisco acquired the KC,FS&M and had laid tracks to Afton, creating an artery which would cause 25-30 trains to pass through Miami daily.

In 1900, Charley Doan opened a tin shop. In 1947, he sold out and started a new business with his nephew. The nephew’s son, Phil Trussler, is still running Trussler Services, a connection of 118 years! Read the details here. The Ottawa County Ice Company opened up at Central and NE D about then. Part of its structure is still standing.

By 1902, Millner Brothers had a hardware store located on N Main. Ed Millner would sell out to Belk’s 65 years later, an impressive business run.

Botts and Sons sold groceries, boots, and shoes on Main in 1902. In 1908, Floyd Botts left retail and started his own wholesale business. Botts Wholesale was sold in 1977, a 75-year run of sales!

In 1903, the Palace Drug Store opened across the street from the opera house, at 1 N Main. By 1912, it had been replaced by Hadley Drug. In 1929, Crown Drug purchased Hadley’s. And in 1966, Zip Discount Drugs replaced Crown, and stayed open until some time in the 70’s. That’s over 70 years continuous use as a drug store. The building presently houses KGLC’s studios.

In 1905, lead and zinc were discovered while drilling north of town on Indian-owned land. That led to the founding of the Emma Gordon Mine, and riches for four investors: James F. Robinson, Charles M. Harvey, George L. Coleman, and Alfred Coleman. Lots more mines would be drilled in that area, and mining would be Miami’s main source of income until the middle of the century.

In 1906, a Mr. H.F. Reniker obtained the first vehicle in town, a one-cylinder Cadillac. Since the streets were prairie dirt which quickly transforms to mud, it was of limited use.

By the time Oklahoma became a state in 1907, Miami had grown from a dream to a town of 3000. When Lykins died in 1909, it was up to 5000.

In 1908, convicted murderer John Hopkins was hanged in the county jail yard for the only legal execution to take place in Ottawa county.

Also that year, W.C. Lykins attempted to deed away ground bordering Central that was being used as a city park to a businessman named Franklin Smith. A lawsuit was filed challenging the legality of the act, and in December, 1910, a decision was handed down from a Muskogee federal judge declaring the land to be city-owned, and thus we kept the park, and would have a nice place to build a courthouse.

Also in 1909, Miami was challenged as county seat by a group of businessmen bent on starting their own town in the center of Ottawa county. The non-existent town was called Hilburn. A special election decided the matter, 1544 to 1072 in favor of keeping Miami as the now official county seat. Hilburn never came to be. That year, the Ottawa County Beacon noted that Miami had better than eight restaurants. I presume that means nine.

On May 6, 1910, the Ottawa County Beacon announced that Main Street had begun to be paved, starting with South Main. The July 8 edition of the paper announced that the paving would be completed the following week. The August 5 edition stated that street paving had been completed on Fourth Street (Later Central). This contradicts a claim that it was completed in 1918. Further supporting a 1910 paving is a mention in the December 23, 1910 Beacon that the city had paid for paving Fourth in front of the city park grounds, later where the courthouse would sit. Plus, the January 6, 1910 edition of The Live Wire announced plans to pave Fourth from West A to East D. However, a mention in the November 28, 1908 Ottawa County Beacon mentions that E. Fourth had a “new brick business street.” Perhaps Central was paved first with bricks? Old brick streets have been unearthed elsewhere in town.

The Central bridge over Tar Creek was also built in 1910. Additionally that year, sewer and gas lines began to be laid in town. By fall, both would be in operation. And the city purchased the private Artesian Water and Electricity Company and got into the utility business. Electricity was only generated at night, there was a call in the newspapers for citizens to request fan service during the day, if enough would, the power would be generated then as well.

In 1911, it was decided that Miami needed a permanent courthouse. T.L. Robinson was awarded the contract to house the facility (for $2900) in the building he was erecting at 1st and North Main, known as the Mining Exchange Building. In 1917, that building was destroyed by fire. Its lot would become the home of the Coleman Theater in 1929. The present-day restored Coleman ranks among one of history’s finest triumphs.

On July 31, 1911, the Electric Arch over Central was dedicated. The sign cost 750 dollars, and its launch was accompanied by a band and two male quartets. The arch was located on East C, so that folks getting off at the Frisco terminal would pass under it on the way uptown. The arch came with lights, and was lit up at night for a time. Apparently frugal city leaders soon put an end to that, but by 1917, the Miami Herald-Record mentioned that it would once again light up the night with a city power plant upgrade.

A year before the Mining Exchange Building fire, a contract was awarded a firm in Muskogee to build a new courthouse on city park land on East Central. A cornerstone ceremony was held on May 31, 1916. By the end of the year, the courthouse was complete, and records were moved out of the ill-fated structure before the fire.

Additionally, in 1911, the cornerstone was laid for the new high school on NE A. The new school opened in 1912, the former school was sold for $625 to George Nicely, who razed it for the materials.

On September 29, 1913, an Oklahoma School of Mines was held at the new Miami High School. Its first night class had 72 attendees. The mining school would eventually come to be known as NEO University.

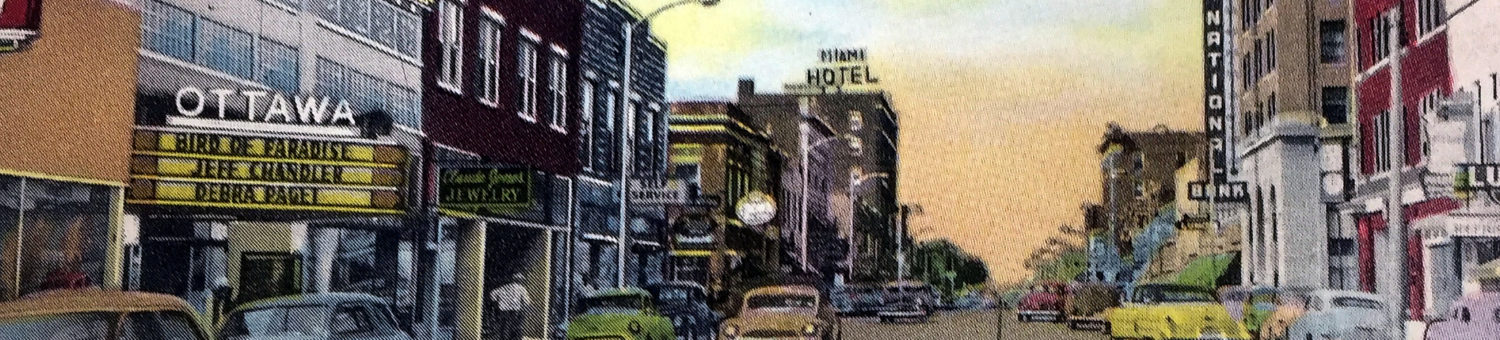

In 1914, a movie theater opened, the Grand, at 12 S Main. After closing in 1933, the Ottawa Theater would open at the same spot 12 years later. In 1917, the Glory B opened across the street. It would eventually become the Miami Theater. Both the Miami and the Ottawa would be gone by 1960.

In 1916, the James S. Mabon Building was completed, which still stands. Also that year, a fellow from Lamar, Missouri by the name of Harry S. Truman was employed as a miner, and paid a visit to the Miami post office to pick up a letter from his fiancee named Bess Wallace.

Additionally that year, the former McWilliams Opera House, which had been sitting idle for some years, was revamped and reopened as the Schmucker Opera House. And Miami was designated as a city through which the new Jefferson Highway would run, stretching from Winnipeg to New Orleans.

Panorama shot about 1917, notice no Hotel Miami, Miner’s Exchange Building, or St. James Place. Click to enlarge.

Panorama from about 1925, notice the changed landscape! Both panoramas shot from the new courthouse. Click to enlarge.

In 1917, construction of large buildings began in earnest. These included the Hotel Miami, the Commerce Building (now St. James Place), the Cardin Building (Security Bank’s longtime home), and the Mining Exchange Building. Incidentally, that building was supposed to be eight stories, but a shortage of material meant that it was limited to five. However, they did make the walls and foundation strong enough to add five more floors.

Additionally that year, there was a strong effort to lure a large Akron, Ohio rubber manufacturer to Miami with a new plant. There was lots of positive talk, but it would be a few more years before that would actually happen. The next year, it was announced that the local banks couldn’t provide the necessary $100,000 in credit, and also the town wasn’t quite big enough yet.

In 1917, Miami was added to the route of the Ozark Trail, one of the first major highways. In 1918, three stucco Ozark Trails monuments were erected at the intersection of Main and Central, also by Riverview Park, and at North Main and 3rd. These were placed at the behest of Monte Ne, Arkansas magnate Coin Harvey, who was the driving force behind the traveler’s association. The Central monument lasted a year before being removed as a traffic hazard. Its demise was supposed to be at the hands of a tank, in a demonstration meant to drum up support for the war. The tank failed to topple the well-built monument, however. I’m sure Coin Harvey was pleased. There’s no record of when the other monuments were removed.

An additional thing to note about 1917 and 1918 is the absence of grocery store ads in the paper. Meatlesss and wheatless days had been declared by the government during the war, and grocers evidently chose to just stop advertising, and demand must have been automatic.

According to an article in the April 26, 1918 edition of the Miami Herald-Record, Miami’s population went from 5,572 in early 1917 to 12,206 a year later, for a one-year jump of 150%.

In 1919, Miami Baptist Hospital opened. The Oklahoma, Kansas, and Missouri Railroad was purchased by Miami stockholders, and would soon become the NEO Railroad. Also, by that year, a painter named John (Joseph) Wilson (who once drove a Butterfield stage coach) was running a contractor business. In addition to creating Wilson Paint and Wallpaper, one of Miami’s most successful and well-loved businesses, he also passed his genes on to his grandson, Charles Banks Wilson, who used them in a more artistic way.

Ozark Trails pillar, shortly before it was removed in 1919

Additionally, in 1919 the governor signed a decree officially authorizing the Miami School of Mines.

In 1920, downtown Main and Central were lit up by streetlights for the first time. The Herald-Record announced in July that the west half of town had been paved, and the east was next. In August, work began for the three dirt streets surrounding the courthouse.

In 1921, the public library opened at its current location. It was replaced by a mid-century-modern rework in 1963. The twenties also saw the arrival of creameries, a meat packing plant, a cheese plant, a bread bakery, a Coca-Cola bottling plant, and two present-day financial institutions: First National Bank, and Security Bank and Trust Company. Additionally, Nott’s Grocery opened in 1926, and continues to be a favorite Miami business. And mention should be made of J. Earl Sandmire, who opened a gas station in 1928 at the corner of 3rd and S Main, and who was still running it 40 years later.

1922 saw the opening of the diminutive 9′ wide paved highway to Afton.

In 1923, a dam was completed across the Neosho River, forming Lake Miami, and frustrating thousands of spoonbills which were used to migrating through town. The dam can occasionally be seen today below the backed up waters from Grand Lake.

By 1924, a paved highway was in place to Commerce. Additionally that year, the Miami Daily News and the Miami Record Herald merged to become the Miami News-Record.

Trolley ad September 24, 1930

On December 17, 1920, the first run was made of the NEO RR trolley. The OK&M interurban train had already been running since 1916 (an earlier trolley had been in place since at least 1909). It featured motorized cars which, according to the newspaper, were less than reliable. The newly formed NEO railroad electrified the line in 1921 and provided much more reliable service. It had a turnaround at what is now Steve Owens Boulevard. It headed north up Main to present-day 4th Avenue, where it turned left and headed north out of town, following tracks which are now abandoned but which still exist to the point of the Goodrich spur, then continuing straight on to the north. It ran through Commerce and Cardin to Picher. In a day of dirt roads, early automobiles, and horse-drawn wagons, it was a welcome way to get around.

1936 NEO ad detailing the closing of the trolley

In 1934, the trolley was gone, its tracks either removed or paved over in some spots, ditched in favor of buses. This December 20 ad from 1936 provides a few details.

In April 1927, Miami had its second most severe flood in its history. A flood in 1904, about which very little has been written, crested with the Neosho 27 feet above flood stage. The 1927 flood peaked at 24 1/2 feet. Highways to the east, south, and west were cut off. Airplanes delivered food from Miami to Welch, Bluejacket, and Fairland. Frisco and the KO&M railroads brought emergency supplies into town via train and motorcars. The southwest part of town was inundated, with some houses flooded to their roofs. The Tar Creek bridge across SE 3rd was completely submerged. Spectators on the Frisco bridge were a problem which the railroad had to deal with.

In 1928, an addition NE of town was platted, and was known as Rockdale.

In 1929, eight blocks of Main and six blocks of Central received street lights on 16′ bronze poles, creating a “white way.” A typical Saturday night downtown included 5,000 shoppers, 976 cars, and the NEO trolley running every thirty minutes.

Miami has much more history, but this would be a good place to wrap up its early years. Stay tuned for more.